On the surface, a Broadway musical, a newspaper, and software may not seem to have much—if anything—in common, but they have one common thread. All are delivered on a fixed schedule. But of the three, software tends to stray the most from the fixed schedule. In this week's column, Jeff Patton says that by focusing on the readiness of the entire product—as done in theatrical performances and when publishing a newspaper—and not just on the completion of the planned bits of work, you can produce software on a fixed schedule that you know is ready to ship.

The opening of a Broadway musical and the morning newspaper have something in common: They both deliver a unique product on a fixed schedule. So why is it difficult for us to do the same in software development?

While I'm no expert on journalism or theater, I know they do a couple things that we often neglect to do in software development, namely focus on the readiness of the entire product and not just the completion of planned bits of work.

I learned to apply the same kind of thinking working on software for brick and mortar retailers. These retailers often had hundreds of physical stores that ran our software. Each project had many risks. Could our software scale to hundreds of locations and millions of transactions? Could unskilled users quickly learn the software without much training or delay of business in the store? Our biggest looming concern was launching by Thanksgiving. If the project wasn't completed and rolled out by then, we'd need to wait another year. Retailers weren't willing to take on the risk of making major changes to their system during their busiest time of the year. They said, our "opening night" was usually sometime in October.

I learn the hard way, by making a mess of things the first time. But from this experience, I've designed three successful strategies that may help you decide if your product is ready to ship.

1. Understand the Big Picture and Focus on the Big Stuff

These days I use agile development approaches. I love the emphasis on breaking down work into small, deliverable pieces using backlog items or user stories, and then getting each done—really done—in a short time frame. But I know none of these little pieces by themselves make a shippable product. Lots of little pieces add up to big capabilities.

Similarly the morning newspaper is composed of lots of individual stories, many supported by pictures and each requiring writing, editing, and fact checking. But the paper is organized into sections like international news, local news, finance, entertainment, and sports—big chunks like that.

For software used at point-of-sale by a retailer, our product capabilities included "selling items," "returning items," "collecting payment," and "managing inventory"—big chunks like that.

The first step to finishing on time is to see the big picture of your product as a number of big capabilities. These may be obvious to everyone on your project but often aren't explicit. Get together as a team and decide what they are.

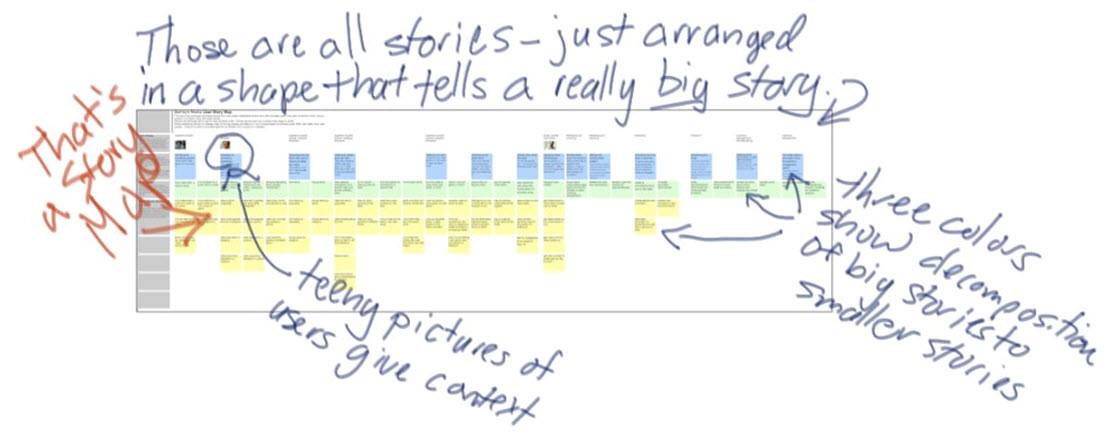

In agile development I use a technique called story mapping to organize my user stories into a big picture that's easy to explain and where all the small stories fall under a big capability or activity that users engage in.

2. Build the Whole Product Roughly to Start

Pretend you've just been cast onto a Broadway musical. Before you were cast, there was likely a script that divided the musical into scenes—the big chunks for a show like this.

In theater it's a bad strategy to start with the first scene, create all the costumes, finish all the sets, choreograph all the dance numbers, rehearse one scene repeatedly until it's perfect, and then move on to the next scene. They'd likely get the result I often see in software development, which is many bits of software completed well but major parts not having started at all. People would hate to show up for the big Broadway show and learning that the director has dropped the last two scenes of the musical in order to finish on time.

The theater trick is to rehearse the whole musical performing and perfecting each number-starting without sets, costumes, or a full orchestra, then adding and improving those things over time. On opening night we're not aware that the costumes could have been better given more time, or that the sets were missing parts that were originally planned. To the audience, the whole thing is complete. We'd never know that in scene four the lead actress was supposed to be wearing a big feathered hat that didn't get finished in time—unless someone who knew the original plan pointed out the "missing scope."

By applying this strategy to software development, we'd focus on building every major capability of a product to a level that wasn't ready to go live but was complete enough to show what the whole product would look like. In an agile environment, I slice stories thinly, back to the raw basics that allow me to see the software working, but not ship it. This is the Broadway musical version of performing the scene on a bare stage dressed in a t-shirt and jeans. Once I can see the whole product at this level, it's time to begin building it up by adding more thin slices to each capability of the product, thus, improving it all.

3. Routinely Assess and Improve the Product's Shipability

Now pretend you're the director of the Broadway musical. The producer phones you a month before opening night and asks you how things are going. If you answer: "We're done with 16 of the 20 scenes," you'd better start looking for another job. What the producer's looking for is some idea of how successful the show is going to be. It's about what happens after opening night. The producer doesn't care that the hat for the lead actress may not be done prior to show time. He only cares if it affects opening night reviews.

In software development we pay a disproportionate amount of attention to the output (the stuff we build) and not enough attention to the outcome (the benefits we want). In agile development, one of the most common ways to assess progress is using a burn-down chart popularized by the Scrum process framework. It's a simple chart that shows how many items we have left to build at any time. Watching the slope of the line showing items built over time tells us how fast we're building. The one thing it can't tell us is if people will like the software when they get it-if the outcome will be good.

In Scrum, the person or people filling the product owner roles are ultimately responsible for a successful product. Like the director of our musical or the editor of the newspaper, their work will be applauded if the outcome is good. Ultimately, the product's success relies on everyone doing well. If you're a scrum product owner, you can help everyone understand how likely success will be with a routine release readiness assessment.

Release Readiness Assessment Recipe

A release readiness assessment keeps the subjective quality of your product visible. The product manager or product owner, supported by a team, performs an assessment every week or two. To do this:

- Gather a small working group who understands the product, and can define success after delivery.

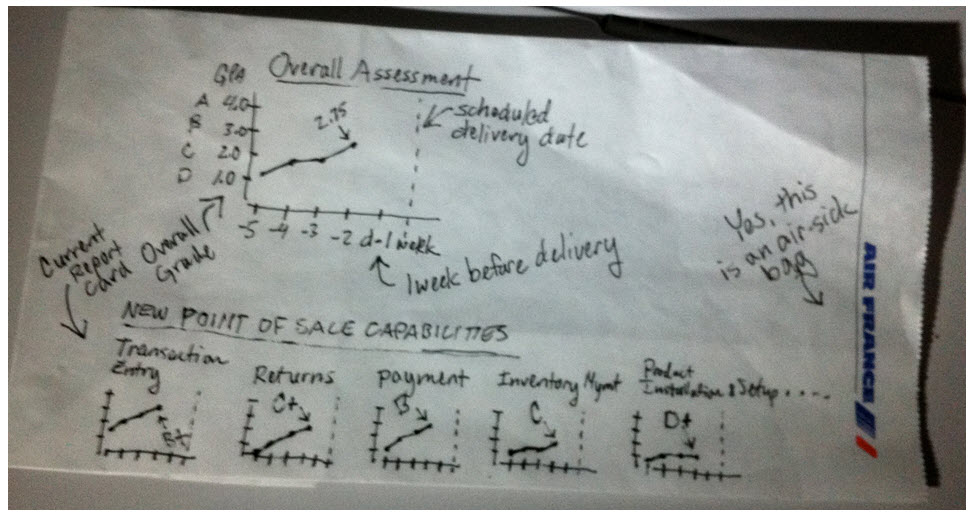

- For each of those big capabilities of your product, consider the product's consumer. Consider what their life will be like after the product's delivery. Will they be unhappy, satisfied, or ecstatic? Together as a product team, discuss and decide on a grade to give the functionality as it stands right now. Try using a letter grade the way US school systems do. A capability that's satisfactory but not fabulous would get a "C." One that won't work at all for its intended audience would get an "F."

- With this current report card of your product, communicate the grades to the entire team. Discuss your plans for the next round of work with the goal being to improve the current report card.

Keep releasability status visible over time by showing current grades, how they've changed over time, and an aggregated grade for the product and how it's changed. The quick sketch above shows how it might look. You don't have to create it on an air-sick bag though.

About the time you get something working in each major product area, you'll be able to perform the first assessment. Create your product delivery plans so that you can do this as soon as possible, ideally before you've used half your time for delivery. Your first report card may have of lots of Ds and maybe an F or two. Don't be too concerned just yet. If you've built a thinnest working slice of your product early, you should have plenty of time to get your grades up before opening night.

At release time, your burn-down chart may not have burned all the way down. There may be a bit of functionality in there-possibly the stuff that would turn a B+ into an A or A-. But that remaining scope is just output. If you've followed the strategies above you'll have delivered on time and secured the best possible outcome for your product.

Additional Reading:

For more on story mapping see "Telling Better User Stories-Mapping the Path to Success," Better Software magazine, November/December 2009.

For more pointers on making functional quality visible, read "Simple Strategies to Keep Quality Visible."